At the end of the day, governments and institutions are intended to ensure the well being of the communities they represent. This section examines outcomes for people since the onset of the Covid crisis.

While much of the most meaningful data on how people are faring will not be available until months after the date it reflects, this section examines key economic metrics from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as well as a timely survey from the U.S. Census Bureau (the Household Pulse Survey) that assesses the human impact of the Covid crisis across America, and an analysis of unemployment benefits relative to basic costs in each county. For each indicator, we provide a brief explanation of findings and implications to weave together an overview of how Americans are faring during the pandemic.

Indicators in this section

- Employment rate by race/ethnicity

- Labor force participation by gender

- Food insecurity

- Likelihood of eviction or foreclosure

- Counties where UI benefits are insufficient for basic costs, by Covid hotspot

- Mental health

The September employment rate of 57% remains below the low of the Great Recession. Young adults experienced an uptick in employment, reaching 31% – roughly on par with one year earlier.

Employment rate, by race and age, Sep 2020

Employment-Population Ratio of civilian, non-institutionalized workforce age 16+, seasonally adjusted

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

In September 2020, the employment rate for adults was only 57%. Though employment rates have grown month by month since April, employment remains below the low point of the Great Recession and well below February of this year, when 61% of all adults had employment.

Just as the Great Recession had long lasting negative impacts on the share of adults with employment (as depicted in this graphic), some economists worry that many adults will become discouraged and stop looking for work all together due to the depth and length of the current recession.1

Young adults aged 16 to 19 experienced better than average employment recovery and by September, this group’s employment rate was nearly the same as one year earlier. In September, employment rates for Hispanic or Latinx adults remained highest at 58% with many employed in essential positions in agriculture, food processing, and janitorial services.2,3,4 White and Asian adults had employment rates of 57% while Black employment was stagnant at only 53%.

The Covid pandemic has pushed many people out of the labor force. Labor force participation, which had been rebounding since April, fell in September – particularly for women.

Labor force participation, by gender, Sep 2020

Civilian labor force participation rate, seasonally adjusted

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Labor force participation indicates the number of adults who are either employed or looking for work and is an important indicator of the health of an economy. During the Great Recession and in the intervening years, labor force participation among men dropped roughly 4 percentage points as many men aged out of the workforce or became discouraged and stopped looking for work altogether.1

From January to April 2020, male labor force participation fell from 71.8% to 68.6%, then recovered to 70.1% by August, but dipped again to 69.9% by September. Female labor force participation fell from 59.2% in January 2020 to 56.3% in April, rose to 57.6% by August, but fell more dramatically to 56.8% by September.

Women are more deeply impacted by the Covid recession because they are more often employed in low-wage service sectors jobs in restaurants, retail, and hotels that have evaporated in recent months. Moreover, 1 in 4 women in the U.S. have children under 14 at home and are disproportionately responsible for at-home childcare duties. This fall, many mothers find themselves unable to work or unable to advance meaningfully in their careers as childcare centers are unavailable or schools require remote learning.2,3

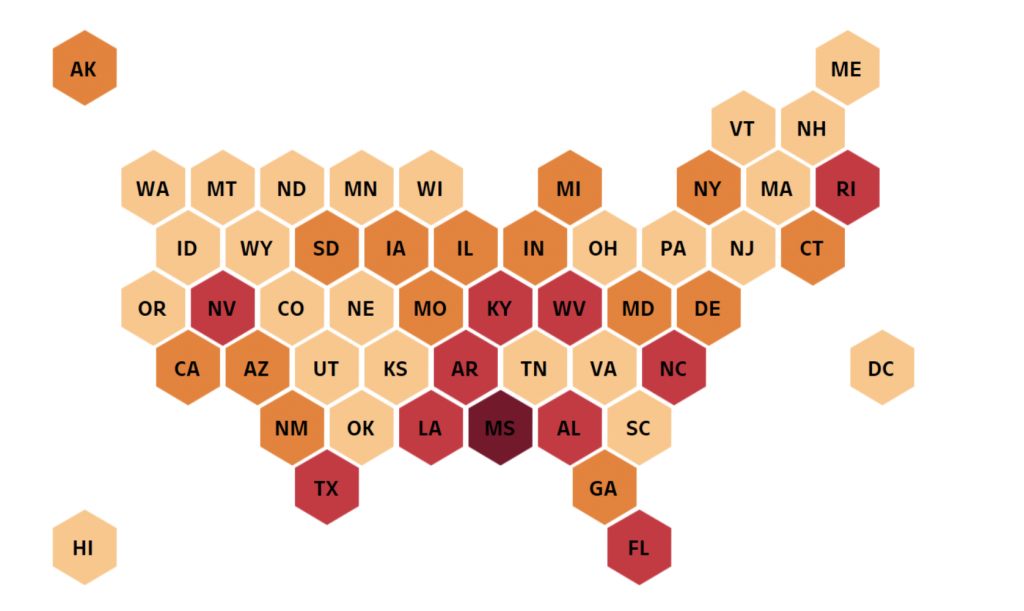

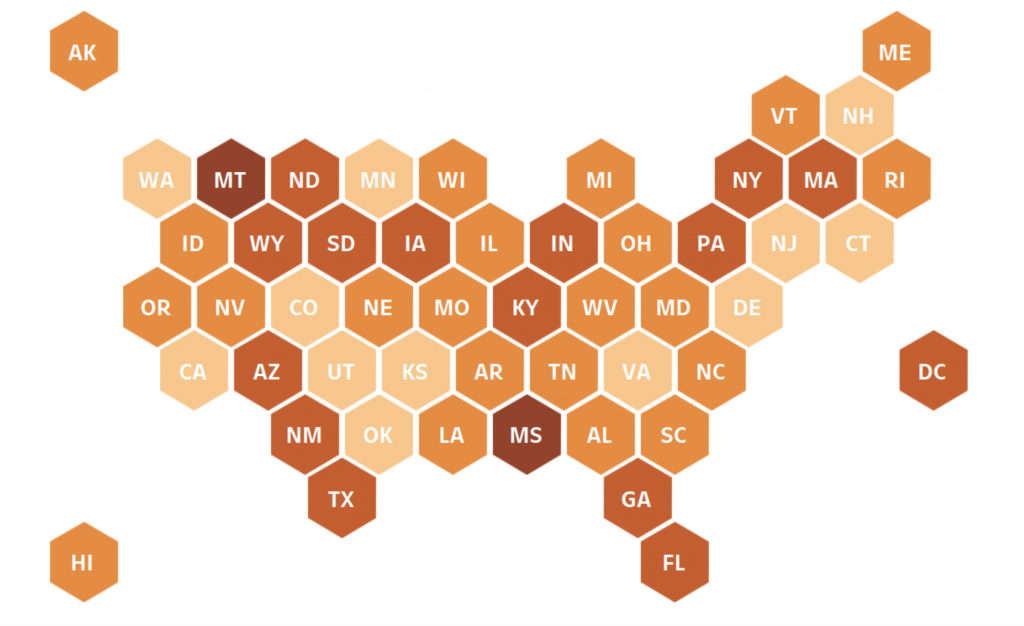

More than 1 in 10 adults report their households have gone hungry during the pandemic. Mississippi ranks highest with 18%, Arkansas and Nevada are next at 15% and 14%, and Minnesota and North Dakota are lowest at 6%.

Food insecurity by state, Sep 30 – Oct 12, 2020

Percentage of adults who report their household sometimes or often went hungry in the last 7 days

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey

Over 10 percent of the United States has reported food insecurity consistently during the past several weeks. States hit hardest tend to be in the South, while those in the Northeast face less, though not zero, instances of food insecurity. According to NPR, “roughly 6% of the population lived in a food desert and 2.1 million households both lived in a food desert and lacked access to a vehicle in 2015.”1 The pre-existing geography of food deserts has been exacerbated by the pandemic, with job losses reducing a household’s ability to cover the basic costs of food.

Though difficult to quantify, the role of food pantries, community volunteers, local emergency food programs, and increased flexibility for federal food programs are most certainly buffering the full impact of the pandemic on hunger.2,3,4 Even so, an estimated 9-17 million children in the U.S. report are sometimes or often going hungry.5 As they are now, during the first phase of the Census Bureau’s Pulse surveys (April-July), southern states were consistently among the most food-insecure.

Not only are there differences in food security across states during the current crisis, but historical data shows a persistent racial disparity, with Black and Hispanic households going hungry at rates twice that of white households.6 For those living in food deserts, a cruel twist of biology comes into play; food insecurity is linked to conditions such as diabetes and obesity, and those comorbidities are also among the most common risk factors for worse Covid outcomes.7,8

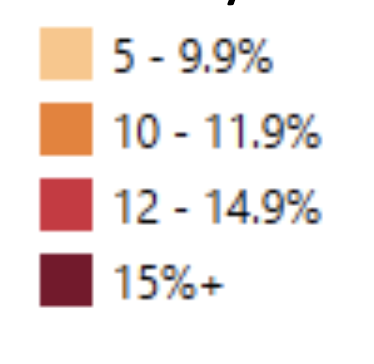

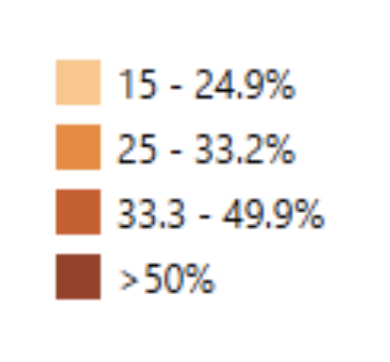

Fully 60% of adults in Montana and Mississippi anticipated they will be evicted or foreclosed upon in the next two months. In 16 additional states, at least 1/3 of all adults anticipate losing their housing during that time frame.

Likelihood of eviction or foreclosure, Sep 30 – Oct 12, 2020

Percentage of adults living in households where eviction or foreclosure in the next two months is either very likely or somewhat likely.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey

With 10 million fewer jobs across the U.S., Americans are feeling very uncertain about their future. More than 1 in 3 adults in 18 states report they are likely to be evicted or foreclosed upon in the next two months. This is true across a wide swath of states. The effects of housing insecurity on children are dramatic. Eviction or foreclosure may force families to suddenly move, begin couch surfing, or even become homeless.1 Not surprisingly this can lead to frequent school moves, absenteeism, and lower test scores for children.2 Children without stable housing are also susceptible to mental health issues, developmental delays, and trauma that can affect children’s future health, education, and employment outcomes.3

On September 4th, the CDC issued a moratorium on all evictions for nonpayment of rent effective September 4 through December 31, 2020.4 However, tenants will still be obligated to pay back rent on January 1, 2021.5 Also troubling is the effect on landlords of nonpayment of rent, and the ultimate effect on banks as mortgages go unpaid.6 The Mortgage Bankers Association reported that since the pandemic began, mortgage delinquency rates have hit their highest point in 9 years.7

Over 50% of the nation’s 2,600 counties deemed unaffordable for those relying on state unemployment insurance are also active Covid hotspots.

Counties where state unemployment insurance fails to cover basic costs, by Covid hotspot status

Includes costs for a two-bedroom home, food, and transportation

Source: USAFacts, New York Times Covid-19 data

Note: Counties with ≥100 Covid cases/100k people in the past week are classified as “hotspots” for this analysis. Blank counties on map are not “unaffordable” for those on state unemployment insurance.

State unemployment insurance pays only 40% of a worker’s previous wages on average.1 In part to motivate workers to continue looking for employment, unemployment insurance benefits are generally lower than a worker’s previous wages. However, the nation has lost 10.7 million jobs since February, and many workers are not able to find employment despite earnest efforts to do so. Congress approved an additional $600 in weekly unemployment benefits, but this support ended in late July. New financial support from the government has not yet been approved, and will likely not be approved prior to election day.2 USAFacts analyzed people’s ability to live off of state unemployment insurance by comparing fair market rents plus the average costs of food and transportation to the maximum available financial support in each county.3 Their data show that in 8 out of 10 counties, the state unemployment insurance is not sufficient to cover these costs.

In those counties where unemployment benefits are insufficient to meet basic needs, housing and food insecurity is likely to be high. The Midwest and deep South are particularly hard hit by these compounding factors on top of the challenge of living in a Covid hotspot (100+ new weekly cases per 100k people). With the national increase in Covid cases,4 many more counties (50% of unlivable counties) find themselves newly designated as hotspots. This marks a 75% increase in“unlivable” counties that are also Covid hotspots, up from 33% in August. With financial support not increasing for those households unable to cover basic needs, and the addition of more Covid cases, inhabitants of these unaffordable counties are likely being hit with untenable situations.

63% of adults reported anxiety over the last week. Those making below $50k per year report feeling anxious at rates 8 percentage points higher than those making $50k and above.

Instances of anxiety, Sep 30 – Oct 12, 2020

Percentage of respondents who suffered from anxiety in the last 7 days

Source: U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey

Mental health has undoubtedly been affected by the Covid pandemic. As many find themselves in more isolated situations, coupled with the stress of the pandemic and the economic downturn, cases of anxiety and depression have increased.

According to the Census Pulse Survey, 63% of adults reported feeling anxiety over the last 7 days. This number increases as household income decreases. Among those earning less than $25K, 72% report feeling anxiety. Children yield additional sources of stress, with 66% of households with children reporting anxiety compared to 60% in households without. Uncertainties catalyzed by the pandemic, such as job insecurity and schools reopening, more heavily impact low income adults and parents with children. Women also expressed feeling anxiety at much higher rates, with 69% of women feeling levels of anxiety, compared to only 56% of men.

The Kaiser Family Foundation found in July that the mental health of 53% of adults in the United States had worsened due to concerns over the pandemic, up from 32% in March.1 They point to a link between social isolation and poor mental health, adding that job loss can exacerbate these outcomes. Psychiatrists writing in The New England Journal of Medicine recently noted that Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) resulting from pandemic anxiety has the potential for long-lasting consequences.2

References:

Employment rate, by race and age

- “What’s the Jobs Outlook this Labor Day Weekend?” Aaronson, Dollar. Brookings. September, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/podcast-episode/labor-and-trade/

- “A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries.” Rho, Brown, and Fremstad. Center for Economic and Policy Research. April, 2020. https://cepr.net/a-basic-demographic-profile-of-workers-in-frontline-industries/

- “A Profile of Frontline Workers in Massachusetts.” Schuster, Mattos. Boston Indicators. April, 2020. https://www.bostonindicators.org/article-pages/2020/april/frontline_workers

- “Profile of Essential Workers in Virginia During COVID-19: Women, People of Color, and Immigrants Are Important Contributors In Front-line Virginia Industries.” Mendes, Goren. The Commonwealth Institute. April, 2020. https://www.thecommonwealthinstitute.org/2020/04/22/profile-of-essential-workers-in-virginia-during-covid-19-women-people-of-color-and-immigrants-are-important-contributors-in-front-line-virginia-industries/

Labor force participation by gender

- “Why Are fewer People in the Labor force during the Great recession?” Nichols, Lindner. Urban Institute. July, 2013. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/23886/412880-Why-are-Fewer-People-in-the-Labor-Force-During-the-Great-Recession-.PDF

- “The Virus Moved Female Faculty to the Brink. Will Universities Help?” Kramer. The New York Times. October, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/06/science/covid-universities-women.html

- “Why has COVID-19 been especially harmful for working women?” Bateman, Ross. Brookings. October, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/essay/why-has-covid-19-been-especially-harmful-for-working-women/?utm_campaign=brookings-comm&utm_source=hs_email&utm_medium=email

Food insecurity by state

- “Food Insecurity In The U.S. By The Numbers.” Silva. NPR. September, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/09/27/912486921/food-insecurity-in-the-u-s-by-the-numbers

- “FNS Actions to Respond to COVID-19.” USDA Food and Nutrition Service. July, 2020. https://www.fns.usda.gov/disaster/pandemic/covid-19#:~:text=Pandemic%20EBT%3A%20FNS%20is%20allowing,or%20reduced%2Dprice%20school%20meals.&text=Fresh%20Fruit%20and%20Vegetable%20Program,them%20home%20to%20their%20children

- “New Orleans launches program to distribute 60K daily meals this July; here’s how you can sign up.” Williams. The New Orleans Advocate. July, 2020. https://www.nola.com/news/coronavirus/article_b98d61f2-bbad-11ea-9a8b-fb24801d507a.html

- “Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker announces $3.3 million in grants to address food insecurity from coronavirus pandemic.” Hanson. MassLive. August 2020. https://www.masslive.com/coronavirus/2020/08/massachusetts-gov-charlie-baker-announces-33-million-in-grants-to-address-food-insecurity-from-coronavirus-pandemic.html

- “Tracking the COVID-19 Recession’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. September, 2020. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-recessions-effects-on-food-housing-and

- “Examining the Impact of Structural Racism on Food Insecurity: Implications for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” Odoms-Young, Bruce. Family & Community Health. April, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5823283/

- “Food Insecurity And Health Outcomes.” Gunderson, Ziliak. Health Affairs. November, 2015. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645

- “People of Any Age with Underlying Medical Conditions.” CDC. July, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

Likelihood of eviction or foreclosure

- “Protecting Children From Unhealthy Homes and Housing Instability.” Office of Policy Development & Research. 2014. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/fall14/highlight3.html

- “Reduce poverty by improving housing stability.” Cunningham. Urban Wire. June 2016. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/reduce-poverty-improving-housing-stability#:~:text=Housing%20plays%20a%20critical%20role,it%2C%20there%20are%20terrible%20consequences.&text=Housing%20instability%20can%20lead%20to,low%20test%20scores%20among%20children.

- The Importance of Housing Affordability and Stability for Preventing and Ending Homelessness. The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. May 2019. https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/Housing-Affordability-and-Stablility-Brief.pdf

- “Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions To Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19.” Center for Disease Control. September, 2020. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/04/2020-19654/temporary-halt-in-residential-evictions-to-prevent-the-further-spread-of-covid-19

- “What the CDC eviction ban means for tenants and landlords: 6 questions answered.” Mason. Fast Company. September, 2020. https://www.fastcompany.com/90547069/what-the-cdc-eviction-ban-means-for-tenants-and-landlords-6-questions-answered

- “Eviction Moratoriums don’t solve the problem, they simply shift the problem to someone else.” Chamber Business News. August, 2020. https://chamberbusinessnews.com/2020/08/17/eviction-moratoriums-dont-solve-the-problem-they-simply-shift-the-problem-to-someone-else/

- “Mortgage Delinquencies Spike in the Second Quarter of 2020.” DeSanctis. Mortgage Bankers Association. August, 2020. https://www.mba.org/2020-press-releases/august/mortgage-delinquencies-spike-in-the-second-quarter-of-2020

Counties where UI benefits are insufficient for basic costs, by Covid hotspot

- “Total initial UI claims have risen in each of the last four weeks.” Shierholz. Economic Policy Institute. September, 2020. https://www.epi.org/blog/total-initial-ui-claims-have-risen-in-each-of-the-last-four-weeks-congress-must-act/

- “Stimulus Deal Before Election Hangs on Pelosi’s Tuesday Cutoff.” House. Bloomberg. October, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-19/stimulus-deal-before-election-hangs-on-pelosi-s-tuesday-cutoff

- “Where does unemployment insurance go the furthest?” USAFacts. July, 2020. https://usafacts.org/articles/unemployment-benefits-by-state-and-county/

- “Coronavirus Maps: How Severe Is Your State’s Outbreak?” Adeline, Jin, Hurt, Wilburn, Wood, and Talbot. NPR. October, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/09/01/816707182/map-tracking-the-spread-of-the-coronavirus-in-the-u-s

Instances of anxiety

- “The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use.” Panchal, Kamal, Orgera, Cox, Garfield, Hamel, Muñana, and Chidambaram. Kaiser Family Foundation. August, 2020. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/

- “Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic.” Pfefferbaum, North. The New England Journal of Medicine. August, 2020. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2008017